Take a walk on the former spread of Joshua Cowell.

Cowell is — to borrow a term epidemiologists use — resident zero.

He came here 148 years ago in 1863.

Unlike most newcomers today that move to Manteca by crossing the Altamont in Tesla sedans and such, Cowell hoofed it on foot over the Sierra from Nevada’s Carson Valley.

Just like those plunking down $450,000 to $1.2 million today to secure their place in what was once known as the sandy plains, Cowell came here in search of a better life and to raise a family.

Along the way he managed to plant the seeds not just for a large farming operation but also for what is now the City of Manteca that’s on the verge of 90,000 residents.

Cowell’s farmhouse is no longer standing. In its place is the Bank of America.

This is the first of many reasons why you can get a good perspective on Manteca by contemplating the transformation of the blow sands that once generated endless tumbleweeds. The sandy plain was home to so many rabbits threatening crops that annual hunts sponsored by farmers for years ended up having in excess of 5,000 of them killed in a single day.

If Cowell’s home were still standing it would still be at the heart — and rough geographic as well as population center — of Manteca. While it isn’t obvious to many, the original core of the city isn’t in decay. It simply is older with homes, buildings, streets, and infrastructure standards of a number of bygone eras.

Cowell was the community’s founder, first mayor, farmer, businessman, developer and the man whose parlor doubled for years as a funeral venue. His backyard housed fire brigade buckets and the town’s fire bell. That’s why he would likely have a few thoughts about what is going on today in Manteca.

Among them is the incessant grumbling among some that Manteca is somehow in the toilet due to the community’s level of amenities. Freely translated, Manteca isn’t a clone of places like Livermore, Pleasanton or any other Bay Area community residents flee or Bay Area cities whose amenities longtime Manteca residents covet.

It’s not that Cowell would have disdained what some might label as gingerbread wants as opposed to basic needs of a community. By all accounts while Cowell was a resourceful and practical man but he also partook in community social pleasures and gatherings.

He’d probably take a look around and come to the conclusion Manteca residents are living pretty well thanks to being in a full service city. Things can always be better, but when it comes to what is needed day in and day out Manteca for the most part is doing better than just fine.

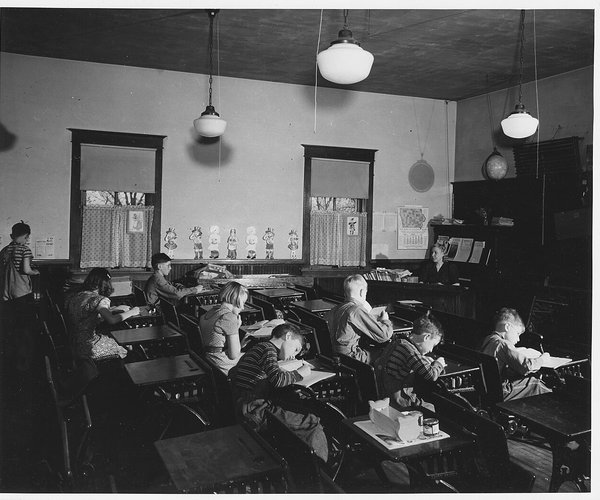

Yes there is clearly street maintenance that needs to be done. That said the big cry and hue in the early days of cityhood was regarding the need to oil the dirt streets to keep the dust down and the need to grade them to eliminate rough spots and potholes. Cowell might give streets an A-plus based on the first asphalt versions that popped up in the 1920s. It is more likely if he had the perspective of what went on after his death until today Cowell would likely say Manteca is doing OK.

As a forward thinker he’d probably advise the current council to come up not just with a game plan and extended hand to the state to pay for street upgrades but also ways to collect local money to do the work.

Cowell would really be impressed with the fire department. The buckets and hose carts are long gone as is the need to clang the fire bell to summon all hands when a fire breaks out. Today Manteca has a fully staffed paid fire department complete with a 100-foot aerial truck. Industry experts have conferred its next to highest rating on Manteca’s Fire Department.

There is no longer a need to keep hunting every so often for a new night watchman at a salary of $35 a month. Manteca now has a professionally trained full-time police department.

Cowell’s outhouse — and those of neighbors in Manteca prior to the 1920s — is long gone.

The same can be said for individual as well as “town” wells. As for the quality and safety of the water, just a stone’s throw or two from where Cowell’s pump house once stood the city has an arsenic removal facility cleaning the naturally occurring element from the water. That’s in addition to well head treatments and cutting edge technology treating surface water from the Stanislaus River watershed that is blended with what water Manteca pumps from the ground.

Cowell and his contemporaries knew transportation was what was needed to take a wide spot in the road and make it a bustling hub.

And back in the 19th century if you weren’t on a railroad line with a stop the community you labored to create with neighbors was doomed to wither on the vine and eventually fade away from maps.

They were able to convince the railroad to allow a milk stop at where Yosemite Avenue crosses the track stop today complete with a platform and a retired boxcar minus the wheels to serve as the station.

They wanted to name it Cowell Station in honor of Joshua Cowell. But there was already another Cowell Station down the line. That is where Manteca came into play.

As the story goes, the next thought was to promote the region’s abundance of dairies that were shipping milk to San Francisco. The decision was made to name it either after the Portuguese or Spanish word for butter which would be “Manteiga” or “Mantequilla”. The railroad supposedly shortened or misspelled it as “Manteca” when they printed the first tickets for the stop.

Given “Manteca” means lard in Spanish and actually “butter” in some regions where Spanish is spoken, there’s a strong likelihood a prankster at the railroad shortened the name or it was initially requested by those who advocated it for the regional definition.

At any rate the tracks right behind where Cowell built his house is where the Manteca Transit Center now stands. Within two years Altamont Corridor Express trains headed to Sacramento and San Jose will start stopping there on weekdays.

Given well-paid commuters and the movement of products by rail are now a lot more vital to the Manteca economy than dairies, Cowell would be ecstatic.

All in all when it comes to the basics as well as leveraging its location and harnessing various modes of transportation Manteca is doing well.

Perhaps if we stopped spending so much time beating each other up and dissing were we live, we could channel that energy into making Manteca even better.

This column is the opinion of editor, Dennis Wyatt, and does not necessarily represent the opinions of The Bulletin or 209 Multimedia. He can be reached at dwyatt@mantecabulletin.com