Forty-nine years ago in February I became the sports editor of the “weekly squeak”, the name that almost everyone in Lincoln called the News Messenger that has been publishing every Thursday since 1891.

It’s not as a big deal as it sounds. I was a high school sophomore at the time. I was paid a dollar for every photo that ran, a dollar for every roll of film I processed, and 15 cents per column inch. Depending upon the season it was 1½ to 3 pages a week.

By the time I started my junior year I was covering Lincoln City Council and Lincoln Planning Commission meetings at 15 cents an inch as well.

It was a bit of a challenge. They met on Tuesday nights at 7 p.m. and usually didn’t finish until well past 10 p.m. I had to go back to the office and pound out — if you’ve ever seen me type “pound” is an apt description — a story that was typically 24 plus inches as the News Messenger went to press early Wednesday afternoon.

I’d usually be through by midnight. And if I didn’t get my homework done before I went to the council meeting, I’d be up until 3 o’clock or so just in time to get four hours of sleep before heading to school.

The minimum wage back in 1972 was $1.65 an hour. Based on five hours each time I covered a council meeting I was making 60 cents an hour. It was fine by me. I was a correspondent and not an employee. I was having the time of my life. Besides, there weren’t very many opportunities for a 15 year-old to work on an actual newspaper.

Between feature stories, sports, city hall coverage, photos, and film processing I made about $250 a month. I was able to add a gig as the Lincoln sports correspondent for the Roseville Press-Tribune on top of that my junior year that led to me being hired at $1.65 an hour my senior year as the daily’s Rocklin city hall reporter plus the backup reporter for Roseville city hall stories.

Those three jobs were all on top of being the editor of the Lincoln High school newspaper called Zebra Territory and juggling a fairly extensive number of extracurricular things at school.

Lincoln at the time had 3,000 plus residents, roughly the same population it had since the 1870s. It was the type of town that if you were shopping or dining downtown when Justice Court Judge Stewart had a jury trial and he was short jurors you ran the risk of being pressed into duty by Emmett, the justice district constable, as long as you were of age.

The News Messenger at the time had over a 100 percent penetration of the city’s households. While that sounds a tad daffy, it wasn’t. If you wanted to know who got speeding tickets or who was hauled in front of the judge for some other offense and you couldn’t wait until the mail came on Thursday you’d be among those that hit the three grocery stores that were open until 9 p.m. on Wednesdays and would grab a copy of the paper for 15 cents so you could find out what had happened.

Rest assured in a town that small with another 3,000 or so folks living in the 196 square miles of the Western Placer Unified School District that included Sheridan and a slew of “places” with rural homes and farms strung about that were named for their community halls that were all built in the 19th century you probably already knew just about everything that was in the paper.

That in includes the results of Lincoln High games, weddings and births. There were even rural columnists — my favorite was Bertha Newcomb — who would write columns about the coming and goings of places like Mt. Pleasant. She’d share how someone had people over to see their new carpeting or share how the pastor of their rural Baptist church had a new garden.

I thought it was all quite normal and exciting.

When my oldest brother went off to Cal Poly San Luis Obispo my junior year, he’d come home and share stories about how guys in his dorm couldn’t wait for his mail to arrive on Mondays as it usually brought the News Messenger.

They thought it was hilarious to see if the front page had a story about the city dump being open. Richard’s dorm mates were convinced it was the funniest thing to put in a newspaper let alone the front page. Knowing whether you could haul stuff out of your yard that weekend was news that people wanted since the city only opened it to the public occasionally.

I’ll concede they did have legitimate reasons to laugh at times.

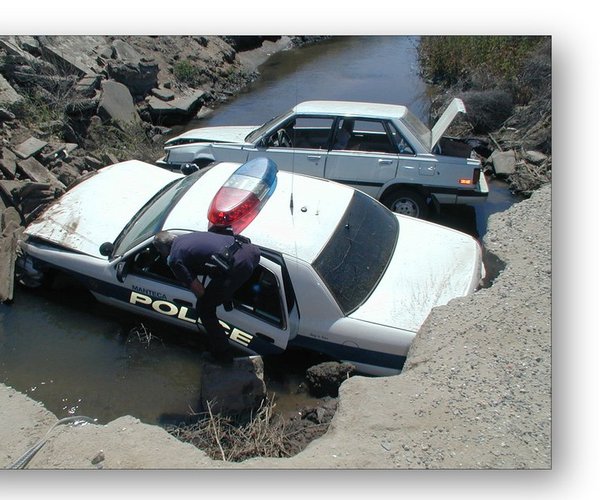

There was a two-month stretch in 1973 when the Lincoln Police Department managed to wreck both of their squad cars — a 1969 Ford Galaxy and a 1971 Chevrolet Impala — as well as a 1964 Chevy Impala that had been retired and repurposed as the city manager’s car that was pressed back into service when they needed the wheels.

The first accident put the Galaxy out of commission. The officer driving it was transporting someone they had arrested to the Placer County Jail in Auburn when they cutoff another car on Highway 49 that happened to be driven by the presiding Superior Court judge.

The Impala was history two weeks later. The Lincoln officer on duty was called in by the CHP and sheriff’s department to help in the search for an honor farm inmate that had escaped from a work detail at Sheridan Cemetery. The local officer spotted the escapee walking along the far side of the Southern Pacific railroad tracks midway between the curve by Nader’s Ranch and the Lincoln clay pits.

The officer turned off Highway 65 — it was actually Highway 99 East back then — and up onto the tracks where he jumped out and successfully chased down the escapee.

Did I mention the officer didn’t go across a grade crossing on a road? Also unlike the train tracks through Manteca, the track bed wasn’t just slightly built up but was a good six feet or so above the surrounding grade. That was due to the heavy clay soil that creates pooling issues after raining.

By the time the CHP and sheriff’s arrived and put the escapee into the sheriff’s unit, the Lincoln officer realized his patrol car was stuck on the tracks that happened to be a heavily traveled mainline where trains often reached 65 mph.

No one thought to call the yard master in Roseville to radio any trains that might be heading down the line. Instead they spent a futile 10 minutes or so trying to push the car off the tracks before a train came into sight around the curve. One does not stop a 90,000 ton freight train barreling down the tracks at 65 mph on a dime. The engineer laid on the horn like there was no tomorrow when he spotted the car and activated the brakes.

They retrieved parts of the police car over a mile stretch.

The 1964 Impala was put back into service. A week later an officer at night was chasing a motorist without any lights on who would not pull over. The pursuit went out of Lincoln on Nicolaus Road.

The driver obviously knew the country roads and the officer didn’t.

Ten miles out of town and in Sutter County the officer found out the hard way that the car he was pursuing did not have brake lights that worked. As the driver navigated a sharp right in the road that headed toward East Nicolaus High, the officer went straight. He ended up airborne and landing in a South Sutter Irrigation District retention pond.

Stories about those crashes got big laughs at Cal Poly, but not as big as the follow up story.

Lincoln Police Chief Bob Jimenez asked Sheriff Scott if his department could borrow a sheriff’s unit while awaiting delivery of two used CHP units. The sheriff obliged with one condition — the patrol unit would come with a deputy who was the only one that would be allowed to drive it.

Like I said, it was great fun working as a high school kid for the “weekly squeak.”

The opinions are of Editor Dennis Wyatt and not necessarily those of the Bulletin or 209 Multimedia.