Climate change wasn’t a concern back in the 1940s.

Gasoline was cheap in comparison to wages.

Burn barrels populated backyards in towns and even cities.

Schemers, with the help of engineers, were busy coming up with ways to carve up — they’d say transform — the California landscape.

It was in that decade that the idea of constructing a bypass of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta first surfaced.

The object was to take water runoff from the Sacramento River basin that was flowing into the sea — boosters would say wasted on the assumption the forces of nature would be imbeciles if they were human — and divert it into basins south of the Delta.

Basins, such as in the southwest San Joaquin Valley, so farmers can farm even more land that their own water basin can support.

That’s where irresponsible farming practices that took Tulare Lake — once the biggest body west of the Mississippi River until the late 1880s — made it vanish.

Also, basins such as Los Angeles that had overtaxed its water supplies so much that even after desecrating Owens Lake and taping into Colorado River water still wanted more water to support more growth.

In 1960 after more than a decade of engineering and politicking, the State Water Project moved forward.

It included a 400-mile aqueduct to serve as the backbone connecting storage facilities to capture runoff in the Sacramento River watershed and storage to serve users.

All of that was built except for the Round Valley Reservoir on the Eel River that Ronald Reagan blocked when he was governor.

But there was a third element that was also identified.

It’s expressed purpose was to maximize water siphoning from the Delta so it wouldn’t be “wasted”.

Funny how one man’s waste is another’s lifeblood.

The water, the third element would convey, targeted supplies for 448,560 acres of some of the world’s richest farmland as well as the economies of people living in and around the Delta.

It also supports a rich, diverse, and fairly unique ecosystem that makes up one the largest inverted deltas in the word and the only delta in the Western Hemisphere on the Pacific Ocean.

You might think such a factoid is for the birds and you’d be right. It is a major component of the Pacific Flyway.

The third element is known as the Delta Conveyance Project.

Gov. Pat Brown was able to launch the State Water Project in 1960s minus the conveyance segment.

It’s a water system that has gotten along without a Delta conveyance project for 65 years.

His son, Gov. Jerry Brown, tried to finish the work his dad started. The Peripheral Canal, though, got walloped by a statewide vote in 1982.

During his second eight-year stint in Sacramento, Jerry Brown re-floated the conveyance project by literally trying to bury it.

That gave life to the Twin Tunnels that were unceremoniously blocked by Delta and north state interests in 2018.

Gavin Newsom, acting at first in his initial month as governor as if he wanted to kill off a questionable water project, brought it back to life.

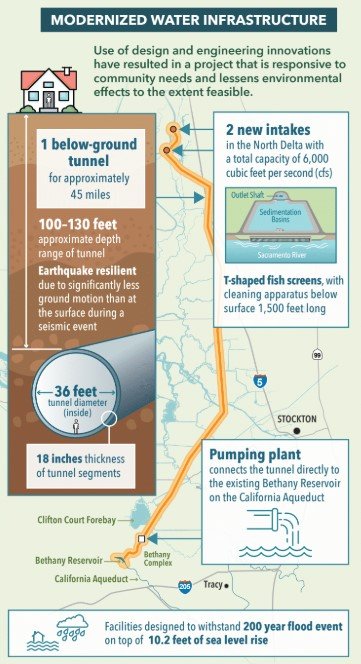

Newsom’s reincarnation is a single tunnel.

Given it is focused on a need identified in the 1940s, it should really be called the Myopic Tunnel.

Today the conveyance project is portrayed on state websites as a defense against earthquakes, rising sea levels, and the forces of climate change to assure the uninterrupted flow of water.

It is, however, for the uninterrupted flow of water for farmers and urban users out of the natural water basin, and not for Californians in this area of the state and the wildlife they cherish.

Imagine if someone wanted to build a desalination plant to address south state water needs on the coast in Huntington Beach that would stress the beloved coastal ecology that Southern Californians cherish.

They’d probably rise up and kill the project which is exactly what they did.

The state websites note how the tunnel would keep water flowing to 750,000 acres of farmland hundreds of miles from where the water will flow out of a 40-mile tunnel, into Clifton Forebay northeast of Tracy and then be diverted into the California Aqueduct.

They didn’t mention the 448,560 acres of farmland in the delta that the conveyance project imperils.

Consider the words of a politician that most people might not admire if they are vested in the Delta wanting to protect its vibrant ecological system and protect local farming.

Newsom called the conveyance project in December 2024 as “the most important climate adaption project in the United States of America.”

The only problem is building it will contribute to what would become California’s most massive climate disaster.

It would make the Delta more brackish and undermine the ecological system.

And riparian rights would not be for fresh water but salt-laden water that kills plants and trees while rendering soil sterile in the long run.

The south state and corporate farm interests are worried rising sea levels will disrupt their flow of relatively salt free fresh water due to rising sea levels.

Official state modeling has the sea level rising as much as 10 feet by 2100.

Most places along the California coast won’t get much sea water inland thanks to ground that starts gaining elevation at the edge of beaches to rise to towering mountains.

In the Delta, official state models show the sea reaching as far east as Stockton and Lathrop.

The tunnel saves the south state and corporate farmers and decimates the Delta.

A decimation worsened by diverting fresh water that holds back salt water no longer coming into play on its way south.

Yes, the islands of the delta are mostly manmade by man’s engineering.

It’s the same engineering that allowed Los Angeles to grow — and to keep doing so — beyond the natural limits of their basin when it comes to needed water.

Why not take a step back and look at investing in solutions not hatched in 1950s sensibilities but with the climate challenges that exist today.

Sea walls at critical points with gates at critical junctures to keep salt water intrusion away from water headed south via the California Aqueduct was rejected early in the environmental review process.

Why not expand on such a solution and protect the Delta while protecting the south state’s important water supply from climate change at the same time?

A more holistic approach to weathering climate change should be on the table for all of California.

Call the conveyance project anything you want — the peripheral canal, the twin tunnels, the tunnel, “the most important climate adaptation project” in the USA, or “a great, big beautiful pipe”.

But at the end of the day it’s all about more water for corporate farmers and to fuel even more south state development.

This column is the opinion of editor, Dennis Wyatt, and does not necessarily represent the opinions of The Bulletin or 209 Multimedia. He can be reached at dwyatt@mantecabulletin.com