Half Dome is not in an amusement park.

It’s part of the wilderness that is within the 1,169 square miles cordoned off by the boundaries of Yosemite National Park.

To reach the 8,846-foot summit of the iconic granite monolith, one must cover the final tenth of a mile that covers an elevation gain of 400 feet with a staggering 75 percent grade.

Earlier this month, a 20-year-old experienced hiker from Arizona died descending Half Dome after getting caught on the summit when one of the Sierra’s notorious afternoon thunderstorms, and sudden downpours, that seemingly come out of nowhere.

On the way down, numerous news accounts stated “she slipped on a wet part of the rock” and fell down the mountain some 300 feet to her death.

In a storm, all of Half Dome is wet.

And because it’s a monolith rock, the surface is completely smooth.

The woman became the 26th person to die since 1919 using the cable system, necessary for hikers per se to reach the top. At least two others have died after being struck by lightning on the summit.

Around 50,000 people hike Half Dome every year, restricted by a lottery system, limiting the route up the cables to 300 people a day — 225 hikers and 75 backpackers.

During the past 126 years, probably well over 2 million people have used the cables.

Her father described the cable system as being “unnecessarily dangerous.”

The inference, of course, is the National Park system can make the ascent safer.

But if there is a way of doing so, it likely would increase the death toll.

It’s because the less serious you take the descent or ascent by allowing yourself to be distracted, the more dangerous it is.

That doesn’t mean to imply the hiker wasn’t serious or paying attention.

It’s just that when anything is made “safer” people develop a false sense of security.

A greater level of comfort always seems to have unintended consequences.

The hiker’s father was quoted as saying “descending the cables with any bit of water, I think, is just an accident waiting to happen.”

That tends to be an issue with smooth granite at a 75 percent grade even without water.

The 600-foot-long “cables” consist of long metal cables anchored to the rock and supported by posts set in 5-inch deep holes, with 2 by 4 inch wooden boards spanning the width placed every 10 feet between each set of posts.

The cable is multi-stranded steel alloy – just like what is used for bridges

Tackling the cables with ordinary tennis shoes won’t cut it. You need soles that grip.

Gloves help avoid getting blisters. More importantly, they prevent you from losing your grip.

Going outside the cables to pass someone severely increases the chances of your day — or more precisely your life — not ending well.

There are more than a few people who opt to use a mountaineering harness to clip themselves to the cables as they go.

Short of installing an escalator where each person is tethered in some fashion, there is arguably no other way to make the last tenth of a mile safer to cover on foot.

This is wilderness, not a ride at Disneyland.

Between 2007 and 2024, there were 4,213 deaths in the national park system.

Yosemite came in at third with 179 after Lake Mead National Recreation Area at 317 and Grand Canyon at 198.

Yet based on deaths per 100,000 visitors, Yosemite ranked 16th on the list of national park system components in terms of risk.

Close to a third or 53 of the 163 Yosemite deaths were by slips or falls.

It is safe to say most were caused by people going where it wasn’t safe to tread.

On the way up to the Half Dome cables using the Mist Trail heading out of Yosemite Valley along the Merced River has been the death of a number of Yosemite visitors.

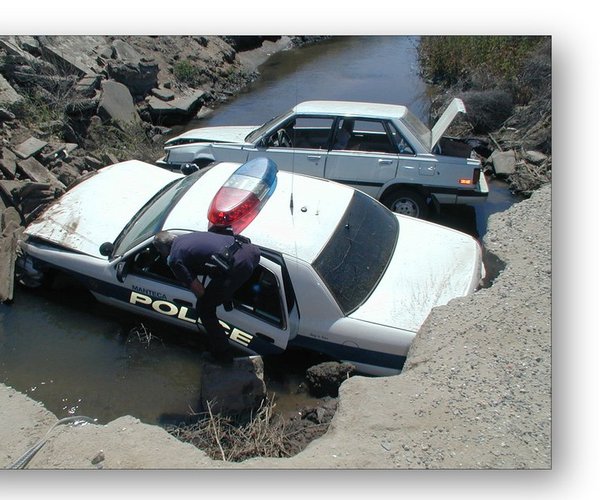

Perhaps the most tragic was when three people 13 years ago this week — a woman from Manteca, a man from Modesto, and a man from Turlock — ended up being swept over the 317-foot Vernal Fall to their death.

It happened in one of perhaps a dozen or so places — if that — along more than 800 miles of developed and “maintained” trails in the 1,169-square-mile park you will find steel rail-style fencing with posted warning signs not to cross.

Two of them crossed the barrier and walked onto sleek granite along the rushing Merced River to get a better photo. One slipped in, the other went to helping her, and a third followed in a bid to save the other two.

Taking photos — or more aptly selfies — in Yosemite have claimed more than a few lives.

People have fallen 800 feet from Taft Point to their deaths on Yosemite Valley’s southern rim while trying to get a more dramatic photo of the sheer drop-off behind them.

Trek into Yosemite enough times, and you can list endless near misses where people didn’t injure or kill themselves.

Many includes those taking photos while hiking along trails with sharp drop-offs.

Then there are those who take shortcuts between switchbacks.

In most cases if they fall they aren’t going to kill themselves.

But the consequence is starting the process of erosion that ultimately can make the trail more dangerous for others.

Occasionally, you will cross the paths of people dressed as if they are going for a leisurely walk in Golden Gate Park heading up toward the 13,061-foot summit of Mt. Dana in the Yosemite high country in the early afternoon as you’re heading back to the trailhead near Tioga Pass as clouds accumulate on the Sierra crest.

They’re oblivious to the warning signs a late afternoon Sierra thunderstorms forming, a state of ignorance that can have serious consequences above the tree line on an exposed mountain side.

The best advice for heading into the wilderness — even if it has a moniker with the safe sounding word “park” at the end — is simple.

Be prepared.

Even then, things can happen.

Life is not without risk.

The National Park Service needs to balance conservation with access.

It has done so with its approach to the Half Dome cable system and limiting access via 300 permits per day.

If anything is “unnecessarily dangerous” it is the assumption by people that the wilderness or hiking up a 75 percent grade isn’t dangerous.

This column is the opinion of editor, Dennis Wyatt, and does not necessarily represent the opinions of The Bulletin or 209 Multimedia. He can be reached at dwyatt@mantecabulletin.com