Albert Hammond nailed it

Seems it never rains in southern California

Seems I’ve often heard that kind of talk before

It never rains in California

But girl, don’t they warn ya?

It pours, man, it pours

Tropical Storm Hilary early this week underscored that premise.

While Hammond was talking about bad luck, it is certainly true of desert regions in Southern California from Death Valley to Anza-Borrego Desert State Park.

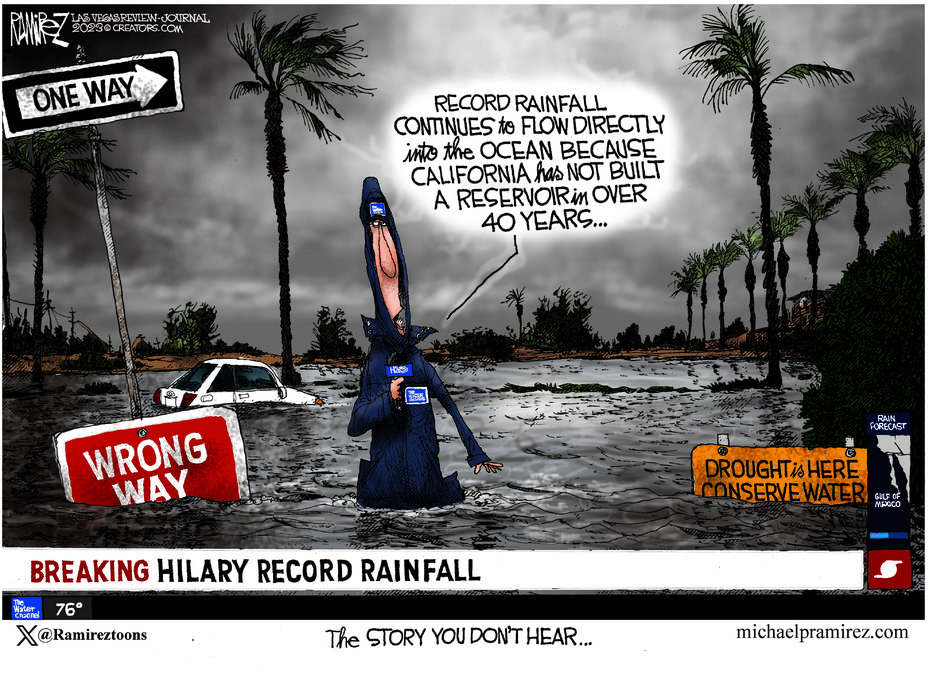

And while Las Vegas Review Journal editorial cartoonist Michael Ramirez has a point in his cartoon accompanying this column, it doesn’t apply to the flooding that just occurred mostly in in the Mojave — the 47,781 square mile desert that goes from 266 feet below sea level to 5,000 feet.

This is not the area where California needs to capture excess precipitation.

It makes more sense to do so in the Great Central Valley through off-stream reservoirs and aquifer recharging.

The average rainfall in the Mojave is 5 inches per year.

That’s a far cry from the Northern San Joaquin Valley where it runs between 12 and 17 inches per year depending upon the area. Stockton, as an example, due to its proximity to the Delta gets 17 inches or 5 more inches than Modesto.

The valley has the added bonus of being where the Sierra and Cascades snowpack melt runoff flows through to reach the Pacific Ocean.

Even without a once in every 80 years or so event with a hurricane making landfall in Southern California as it did this week, those 5 inches of rain typically comes primarily during cloudbursts.

Those cloudbursts hitting the dry desert hardpan resorts in almost all runoff as the ground can’t absorb that much water that quicky.

Toss in torrential runoff from higher elevations so massive and forceful it cuts away at canyon walls and then cuts deep gullies as it runs downhill on the desert floor, building dams or even recharge basins to capture it would be an exercise in futility.

Not only is there inadequate annual precipitation to support reservoir of any consequence, but the way that water works in the desert the debris that it moves would quickly reduce the holding capacity of any reservoir save in a few areas that have already been tapped for water storage.

It is why latching into what happened this week to slam California’s leaders for not building a reservoir in over 40 years to capture excess water not needed to support ecology systems that flows into the Pacific Ocean is kind of a cheap shot.

Not so, however, when it comes to the Central Valley.

Long before “climate change” became as prevalent as the word “dude” in modern day conversations, the concept of large dams in the mountains and higher elevation of the foothills for water storage per se as opposed to flood control had passed.

San Luis Reservoir, completed in 1967 in the Diablo Range foothills west of Los Banos, is the largest off-stream reservoir in the United States with 2 million acre feet of storage.

Even in non-drought years, the water level can get low.

That’s because it is fed by excess stormwater as well as excess snowmelt from the Sierra.

It’s a holding pond, if you will, for water ultimately heading farther south.

The Sites Reservoir — first proposed in the 1950s — is on target to become the state’s next major reservoir.

Nestled in foothills of western Colusa and Glenn counties, it has been inching in earnest toward groundbreaking and a 2031 target completion date for the better part of the last decade since voters approved a statewide water bond in 2014.

It is designed to add up to 1.5 million acre feet of storage that would be used to help supply water for up to 27 million Californians and 500,000 acres of Central Valley farmland. It also would provide water for fish needs in dry years

To get an idea of the impacts it will have, the storms that dropped 120,000 acre feet of water on California the first two weeks of January was enough to serve the needs of 1.3 million Californians for a year.

Most of that water — a large amount of the perception of that fell in the Northern Sacramento Valley — went out into the ocean.

Climate patterns, that are following patterns going back over 800 plus years and verified via the carbon dating of trees, means less precipitation in northern and central California.

That said, while there will be less overall precipitation, there will be more rain at the lower elevations and less snow at the higher elevations.

There aren’t that many sites left where the soil, rock formations, and location are all ideal for larger off-stream reservoirs on the scale of San Luis or Sites.

There are smaller areas such as projects being pursued in the Del Puerto Canyon west of Patterson as well as raising Los Vaqueros Reservoir in eastern Contra Costa County.

The most promising option for increased water supplies is playing out in almond orchards in Stanislaus County where UC Davis researchers are studying the impacts of flooding dormant almond trees with flood waters.

Large scale artificial recharging by injecting water into aquifers through wells as opposed to passively allowing nature to slowly do its thing is also more than promising.

The Kern County Water Bank Authority is an example. It takes “excess” water flows imported form the Kern River and other sources and recharges the aquifer.

It does so — based on soil saturation — at rates that vary from 30,000 to 72,000 acre feet per month.

And although the aquifer is substantially larger, there ultimately is only 1.5 million acre feet readily accessible from recovery wells.

Similar projects elsewhere in the Central Valley are key to California’s future.

Even if it ends up for the most part supplying primarily agriculture, it takes pressure off existing surface supplies for cities and the environment.

It is also less susceptible to losses from evaporation..

The days of big dam projects are over.

Virtually all locations where dams are desirable and the construction for one makes sense from the standpoints of flood control, water supply and financial penciling have been built.

Recharging — and smaller off-stream reservoirs — are what we need.

And just like dams, they need to be placed where they are the most effective.

And that is not, for the most part, California south of the Tehachapi Mountains that became a rare mid-August muddy mess this past week.

This column is the opinion of editor, Dennis Wyatt, and does not necessarily represent the opinions of The Bulletin or 209 Multimedia. He can be reached at dwyatt@mantecabulletin.com