By JASON CAMPBELL

The Bulletin

Mark Alire bragged. He boasted. He teased. He taunted.

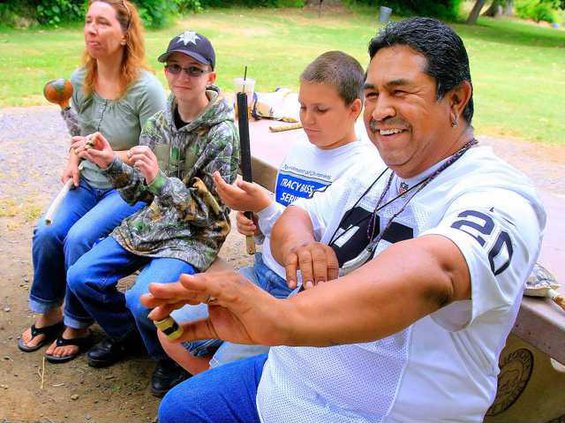

And he did it all while holding the “bones” – small, carved and painted with white and black lines – in his hand as he and the dozen or so people that had gathered beneath a canopy of oak trees in Ripon’s Caswell Park chanted along to a ceremonial Yokut song.

It wasn’t that Alire was trying to be antagonistic. He wasn’t even all that vocal. It was just the spirit of the Native American handgame highlighted by members of the Tachi Yokut Indian community at a cultural event Thursday morning in the park that at one time served as an oasis for tribal members hunting and fishing along the Stanislaus River.

“I want to learn as much as I can about the original people who used to live here,” said the homeschooled 12-year-old. “It’s very interesting to me. I’m curious about how they survived, where they ate, and what they lived on – I’m interested in how they were affected by the California Gold Rush.”

He got more than his fill of information.

Lalo Franco, the head of the cultural preservation department at Santa Rosa Rancheria in Lemoore, spent more than an hour recounting native history and the role that gold discovery played in forcing tribal members south to escape the crush that had begun enveloping them.

While it was San Francisco that hosted the huge population boom and mountain towns like Sutter Creek and Jackson that catered to miners trying to strike it rich, Franco said that the need to feed the millions of people that had descended on Northern California seemingly overnight severely interrupted the day-to-day lives of Tachi Yokuts living in the Northern San Joaquin Valley.

But the story of how Native Americans came to populate the earth was recounted for Alire and his young counterparts through the art of storytelling.

Franco took time to detail how the great golden eagle, believed by natives to be God, took the strengths of individual animals and combined them to form man – the uprightness of the bear, the eyesight of the hawk, the endurance of the deer, the smooth skin of the trout and the nimble fingers of the lizard.

Keeping traditions, like storytelling, alive, Franco said, is one of the ways that the culture hopes to preserve its heritage in a world that has been constantly changing around it for nearly two centuries.

“We have less than 300 elders throughout the valley that still speak the language fluently,” he said. “There’s only so much land left, we have to find whatever we can do to protect our cultural resources. It’s the same story’s that’s been going on all over the world.

“For me, it’s a shame what the human race has been doing to itself for the last 5,000 years.”

Debra Moore, who used to be the park host at Indian Grinding Rock State Park outside of Jackson, said that she hopes outreach efforts like the one Thursday will help put the need for cultural and environmental preservation into focus.

Just last week, she said, the park ranger had to get involved when she discovered people attempting to cut down one of just two sycamore trees remaining inside on the grounds.

“My hope is to get people to realize that they’re destroying this park,” she said. “It’s such a beautiful and natural area and it’s often something that’s taken for granted – people act as if it’s something that they don’t need to take care of.

“We only have two sycamore trees left in the park, and they just started hacking it up. Hopefully this puts the importance of nature into perspective.”

To contact Jason Campbell, email jcampbell@mantecabulletin.com or call (209) 249-3544.

Working to keep heritage of Tachi Yokuts alive