The first treated surface water started flowing through Manteca’s faucets in July of 2005.

It was from a South San Joaquin Irrigation District treatment facility developed in a partnership with Manteca, Lathrop, and Tracy to harness surface water rights from the Stanislaus River watershed the district secured 115 years ago.

It was believed back in 2005 growing water demand would require expansion of the original 40 million gallon treatment plant capacity to start in 2012.

But a series of severe droughts that accelerated water conservation practices by district growers and also prompted cities to impose passive measures to reduce per capita water consumption by as much as 50 percent, reduced demand.

New home construction at the end of the last decade dropped almost to zero throughout the three-county Northern San Joaquin Valley region except in Manteca.

For four years, Manteca was building 250 to 300 housing units a year — more than two thirds of all annual housing starts in the San Joaquin, Stanislaus, and Merced counties — thanks to the dynamics of development agreements with builders.

Those development deals secured sewer treatment plant capacity using the payment of unrestricted growth fees of $5,000 per house that were dubbed “bonus bucks”.

That dynamic prompted financial backers to aggressively fund infrastructure work for seven different developers to allow them to produce ready to build lots.

When the Great Recession hit, builders and investment firms has an averaging of $50,000 to $60,000 “stranded” in 960 developed lots in Manteca to build homes on.

Manteca new home building continued with the city making concessions to help keep private construction jobs flowing as well as tax dollars to avoid layoffs and reduced municipal services.

It meant developers “losing”, in some cases, $10,000 or so per home built in order to “recover” the bulk of the money that was stranded per lot.

It avoided the loss of jobs, it avoided builders and developers going bankrupt, and it allowed investment firms to drastically reduce their potential for financial losses.

It also led to an overnight shrinking of the average square footage of new homes being built in Manteca from almost 3,330 square feet down to under 1,800 square feet.

That made homes affordable for those in a position to handle mortgage payments.

Today, the annual surface water demands haven’t changed significantly since 2007.

That is thanks in part to ground water use that is now coming under a state mandate to have a net impact on aquifers over a set 12-month period.

Conservation measures imposed on homes existing prior to 2013 — whether it is tighter landscape watering restrictions, the switch to more water efficient washers and toilets, as well as turf replacement programs — created a floor when it comes to average household water consumption.

It is why the steady housing growth in Manteca — as well as Lathrop — is prompting SSJID to start preliminary studies to expand the water treatment plant located just west of Woodward Reservoir.

There have been significant spikes in weekly and monthly demands during warmer months when all cities rely heavily in surface water.

Manteca, Lathrop, and Tracy all use well water. Tracy also receives water from the State Water project.

It is against that backdrop the first step is being taken toward a project that could essentially assure an adequate source of water to support adopted Manteca land use envisioned to support a city of 236,000 people.

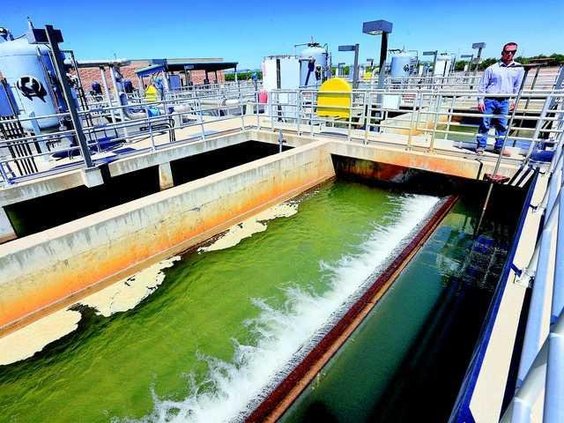

There is no clear timeline toward physically initiating what ultimately would be a 20 million gallon secure phase expansion of the Nick DeGroot South San Joaquin Surface Water Treatment Plant.

The endeavor would increase the treatment plants capacity by 50 percent to 60 million gallons. It would — between groundwater and surface water — be able to support Manteca adding as much as 142,000 residents.

The city currently has 92,000 residents.

The expansion would also address the needs of Lathrop growth as well as bringing surface water to Escalon.

The SSJID board is considering a staff recommendation during a meeting today to proceed with a preliminary engineering study that includes a phased approach to the second phase expansion.

The treatment facility is a joint project of the cities.

The second phase was part of an agreement hammered out in 2004.

The cities paid for the initial phase — and will pay for the expansion — by charging growth to cover the cost of treatment capacity.

Water users in the three cities pay for the water, its treatment, and maintenance/operation costs regarding its delivery to connection points in each municipality.

To contact Dennis Wyatt, email dwyatt@mantecabulletin.com