Manteca resident Larry Dunham’s actions as a private first class in the United States Army on Sept. 20, 1970 were credited with saving numerous lives of his fellow 101st Division soldiers.

For his gallantry in action during the Vietnam War, Dunham was awarded the Silver Star.

And while he received the Silver Star, along with a Purple Heart, it was never formerly presented to him.

That oversight acknowledging his act of valor was rectified Tuesday as the nation celebrated Independence Day.

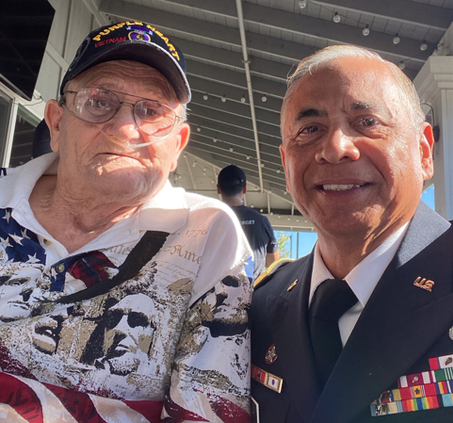

Fellow Manteca resident and fellow Army veteran Retired Major General Eldon Regna formerly presented the Silver Star to Dunham in a ceremony with his extend family present at the Boathouse restaurant at River Islands at Lathrop.

In bestowing the original honor in October 1970, Army Major General John L. Hennessey wrote, “on 20 September 1970, Private First-Class Larry Dunham’s infantry platoon was ambushed at the bottom of a dry riverbed."

“As the soldiers walking point were pinned down by enemy fire, PFC Dunham noted that their machine gun was not firing. Moving from the rear to the front to assist the machine gunner, he was hit by shrapnel from an enemy grenade.“

“Without regard for his wounds, PFC Dunham was able to fix the firing mechanism of the machine gun.”

“Now with covering fire from the machine gun at the enemy, the soldiers in the front were able to escape enemy fire thus saving numerous lives of fellow 101st division soldiers.”

“For this heroic and gallantry in action, Private First-Class Larry Dunham is hereby awarded the Silver Star.”

It was in March of 1970 that Dunham first arrived in Vietnam after finishing his infantry training at Fort Benning, Georgia. Without a designated unit, Dunham and his squad mates bounced around before eventually ending his tour with the 101st Airborne Division.

It was during those nomadic months that Dunham saw the bulk of his combat action while serving in Vietnam. He engaged in more than 30 firefights and heroically garnering a Silver Star for his bravery in a brutal ambush at the bottom of a dry riverbed.

“We were moving through and all of a sudden fire broke out,” Dunham recalled in a 2010 interview. “The guys taking the point were pinned down by fire, and when I came up from the rear I could tell that the machine gun wasn’t firing. I got hit with shrapnel from a grenade, but I was still able to move forward and get to the machine gun and fix the firing mechanism.

“After that, I could lay down fire in the direction of the enemy and give the guys in the front a chance to get out. Essentially I was able to save the lives of those men, but that’s what you did when situations like that.”

Unfortunately, Dunham’s homecoming wasn’t quite as warm.

After arriving at the Seattle-Tacoma Airport on his way home, Dunham was greeted by people in the concourse that threw the contents on their drinks on him as he walked through the terminal in his uniform. It was alarmingly common theme for veterans returning home from Vietnam during the civil unrest of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

When thinking about that experience, and the permanent damage he sustained from his military service, Dunham can’t help but show his emotions.

“Those were the people that I was over there fighting for,” he said in 2010, wiping the tears away from his eyes. “You join the military to protect the American citizens and the way of life that we enjoy. . . But if I had the chance to live my life all over again, I wouldn’t change anything. I love this country and what it stands for, and nothing is ever going to change that.