The $320,000 the City of Manteca is receiving for the sale of 0.67 acres to allow the Loma Brewing Co. to build is the latest dividend in what was arguably the most lucrative municipal real estate deal on the books.

It also gives you an insight into the rationale and perspective of various long-range public-private sector deals the city has fashioned with Great Wolf, BLD lessors, Orchard Valley to secure Bass Pro Shops, Costco, and Living Spaces among others.

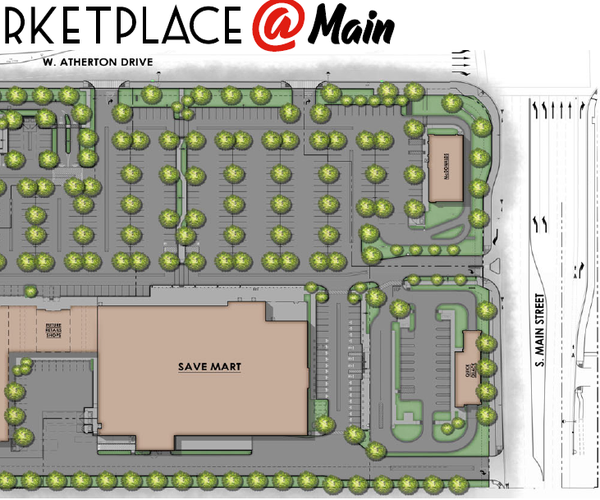

And it gives a clue to the financial motives behind the decision for the City Council on Tuesday to buy 3.67 acres along Atherton Drive just west of Living Spaces.

Long-range investments to generate bigger pay days for the public can be in the form of limited sales and room tax sharing that Manteca imposes end dates on or real estate transactions.

The Loma Brewing Co. development agreement advantage for city — and in turn its 90,000 residents through the collective impact on the city’s ability to deliver services — is via real estate transactions,

The 29,514 square foot parcel that is primarily landscaping on the city-owned Big League Dreams sports complex on the northwest corner of Daniels Street and Milo Candini Drive is part of a 1973 acquisition.

Fifty-one years ago, the city paid $20,200 for 29 acres for use as possible land disposal for treated wastewater.

The city basically paid around a pro-rated $400 for the parcel the City Council approved Tuesday to sell for $320,000 for establishment of a brew pub.

And the $15,601 the city will receive for an annual lease of 32 of the 550 BLD parking spaces so the brew pub can cover basic parking requirements essentially means the city will “recoup” its initial $20,200 investment to buy the land involved in 16 months.

And after that, lease payment for the parking spaces as well as property and sales taxes keep flowing into city coffers.

Granted, inflation magnifies the return on the actual land sale per se.

But if you take the accumulative inflation rate since 1973 of 590.87 percent based on Federal Reserve figures, the constant dollar value of the portion of property the city is selling was bought 51 years ago for $275,441.

That means in constant dollars the city is ahead $44,559 selling the parcel in question for over a 100-fold return over the pro-rated price of $400 in 1973 for the brewing pub site.

Keep in mind the original zoning in 1973 was not commercial as the use is being appraised at today but basic farmland.

Still, that is a significant positive return.

And that does not count the $62,000 that is projected to flow into the city’s general fund and public safety sales tax based on the first full year of operation of the brew pub.

A large chunk of the land the city bought in 1973 — augmented with additional purchases in the same decade — was the linchpin of the 10-year city effort that allowed Manteca to land a $180 million private sector investment for the building of the 500-room Great Wolf indoor waterpark.

By the time 2050 rolls around, the city is projected to have parlayed that $20,200 land purchase into $129.1 million. That would be almost enough to cover the current single year general fund spending two times over.

The land when the city sold in 2016 to Great Wolf after Manteca got all of the necessary environmental hurdles cleared as well as putting infrastructure in place that allowed it to market a shovel ready indoor water park project had a fair market value of $6,750,000.

As part of the incentive to secure Great Wolf, the city sold the property to Great Wolf at a tenth of its value — $675,000. The city had to meet stringent state mandated economic benefit criteria in order to execute the deal.

The other part of the incentive package was sharing of the room tax revenue Great Wolf will generate for a period that ends after 25 years.

Land that was intended originally only to dispose treated wastewater provided Manteca with a private sector employer that created 250 full-time jobs and 250 part-time jobs. The initial payroll the first full-year of operation was pegged at $8.9 million overall.

Then there are property tax receipts.

A $180 million valuation translated a basic annual tax bill of $1.8 million the first year making it the city’s top property tax generator out of the gate. Half of that — $900,000 — goes to the Manteca Unified School District. Roughly $400,000 goes to San Joaquin County. The rest is split among eight taxing agencies besides the City of Manteca.

Manteca expects to incur $350,000 annually in providing non-user fee based city services to Great Wolf such as police and fire. Subtracted from the $592,000 in property and sales taxes the city will receive in addition to its share of the room taxes, it would provide a net flow of $242,000 yearly into the general fund. That is on top of the $2 million annually in room taxes to help fund general city services and $123,000 yearly for Measure M public safety positions.

That means after one year of operation thanks to leveraging land the city bought for $20,200 some 51 years ago, the city has the ability to “net” $2.36 million annually. The land while Manteca owned it did not generate any tax revenue.

Keep in mind that $2.36 million has an asterisk. The bulk of it in the first five years goes to reimbursing growth-related fees the city agreed to cover from its initial year of the original 9 percent room tax split.

The additional 3 percent room tax (to 12 percent overall) that voters imposed through Measure J goes 100 percent to the City.

The original analysis of the deal projected Manteca would net $99.1 million during the first 30 years Great Wolf is open. Thanks to the voter approval of the ballot measure that took the room tax up to 12 percent from 9 percent, the figure is actually $129.1 million as all of the room tax increase goes to the city.

To contact Dennis Wyatt, email dwyatt@mantecabulletin.com